Jamie Dettmer is Opinion Editor at POLITICO Europe.

ROME — “There’s no room for personal considerations,” former Italian Prime Minister Mario Monti wrote last week, appealing to Mario Draghi, his technocrat successor, and friend, in the Chigi Palace not to quit.

“The sense of duty toward the state, toward citizens, is above any other consideration,” Monti declared, although he acknowledged the “understandable bitterness” that “Super Mario” must feel in the face of the “petty games played by various parties, in recent and less recent times.”

It all sounds very Carlylean.

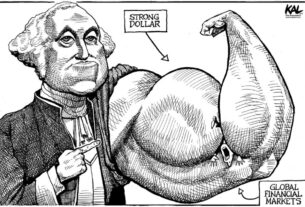

Victorian essayist and cultural polemicist Thomas Carlyle believed “Great Men should rule” and “others should revere them.” No friend of democracy or utilitarianism — “a philosophy fit for swine” he called it — the misanthropic Carlyle had little time for the little people — great men were the drivers of progress and historical development. And consciously or otherwise, much of this week’s support — and hype —for Draghi, coming from the great and good in Italy and across Europe, has echoed the great man theory of history.

Italy can’t do without “the man who saved the euro.”

Indeed, before one of the governing partners, the 5Star Movement, boycotted a confidence vote on a €26 billion cost-of-living package this week, the broad-based coalition helmed by the former president of the European Central Bank (ECB) had achieved a lot. There’s also still much to do to enact the reforms the country will have to implement in order to receive billions of euros in post-pandemic aid from the European Union —reforms that are now imperiled by political turbulence and will be even more so if Italy’s thrown into an early parliamentary election this fall.

Draghi highlighted the achievements of his cross-party government in a 36-minute speech Wednesday in the Italian Senate, praising the coalition unity that had made it possible to face the pandemic’s challenges, an energy crisis, and drought. “The merit for these results is yours, for your willingness to put aside differences and work for the good of the country, with equal dignity and mutual respect,” Draghi told the senators.

Appointed in February 2021 by Italian President Sergio Mattarella, the 74-year-old Draghi has often enjoyed high approval ratings since then — sometimes as high as 65 percent — but he’s never had to face voters. His popularity and program have never been tested on the campaign trail or in polling booths.

There have, however, been regional and municipal elections since his appointment at the head of a broad yet fractious national unity government, and the picture emerging from those elections has been mixed.

In June, a center-left electoral coalition led by the Democratic Party — Draghi’s most loyal governing partner — secured several key wins in local election runoffs, even grabbing the traditionally conservative city of Verona and seven out of 13 provincial capitals, some in the northern strongholds of Matteo Salvini’s League party. Though this was interpreted as a vote of confidence in Draghi, if you dig into the numbers, there’s abundant evidence showing the pro-Draghi left’s successes were, more than anything else, due to splits within the right-wing coalition.

ITALY NATIONAL PARLIAMENT ELECTION POLL OF POLLS

For more polling data from across Europe visit POLITICO Poll of Polls.

Recent opinion polls show that a united right — with the Brothers of Italy, currently the country’s most popular party, at the fore — would likely storm to an outright win in the next general election. And Draghi’s supporters, notably Enrico Letta, secretary of the Democratic Party, seemingly overlook opinion surveys that suggest a sizeable chunk of the electorate haven’t been so happy about democracy being put on hold, and for Italy to be ruled by a man who epitomizes the managerial class — a man who knows best and who marches in lockstep with the reform prescriptions approved by similarly-minded eurocrats in Brussels.

Letta and other backers point instead to a massive public campaign that’s been urging Draghi to remain in office. They say demonstrations in dozens of towns around the country and appeals from top industrialists, professional bodies and around 2,000 mayors truly reflect Italian opinion — democracy by acclamation then, and not by votes.

However, one doesn’t have to be a supporter of Brothers of Italy leader Giorgia Meloni to see some validity in her recent remark that “it’s autocracies that claim to represent the people without the need for citizens to vote, not Western democracies.”

It’s certainly true that under Draghi, Italy has seen a welcome spell of government stability and predictability, but the drawback of managerial rulers is that they often aren’t good at politics and view it as an inconvenience. And Draghi has been especially impatient with elected politicians, seeing any disagreements within his governing coalition as petty rivalries and electoral maneuvers, all just getting in the way of great men governing.

Despite winning the confidence vote this week, and retaining a majority to govern, Draghi chose to quit because some of his governing partners — the populists — wouldn’t accept his ultimatum to refrain from issuing vetos and ultimatums in the future. In other words, no negotiations, no compromises, no trying to observe manifesto promises or being responsive to their own voters. In short, no democracy.

In the end, the man who promised to do whatever it takes when ECB president decided not to as prime minister. And, just maybe, he allowed a little too much room for personal considerations.