PARIS – A viral campaign to “shut down France” on 10 September, now backed by far-left activists and unions, is raising fears of a new wave of protests against the government ahead of tensed budget talks.

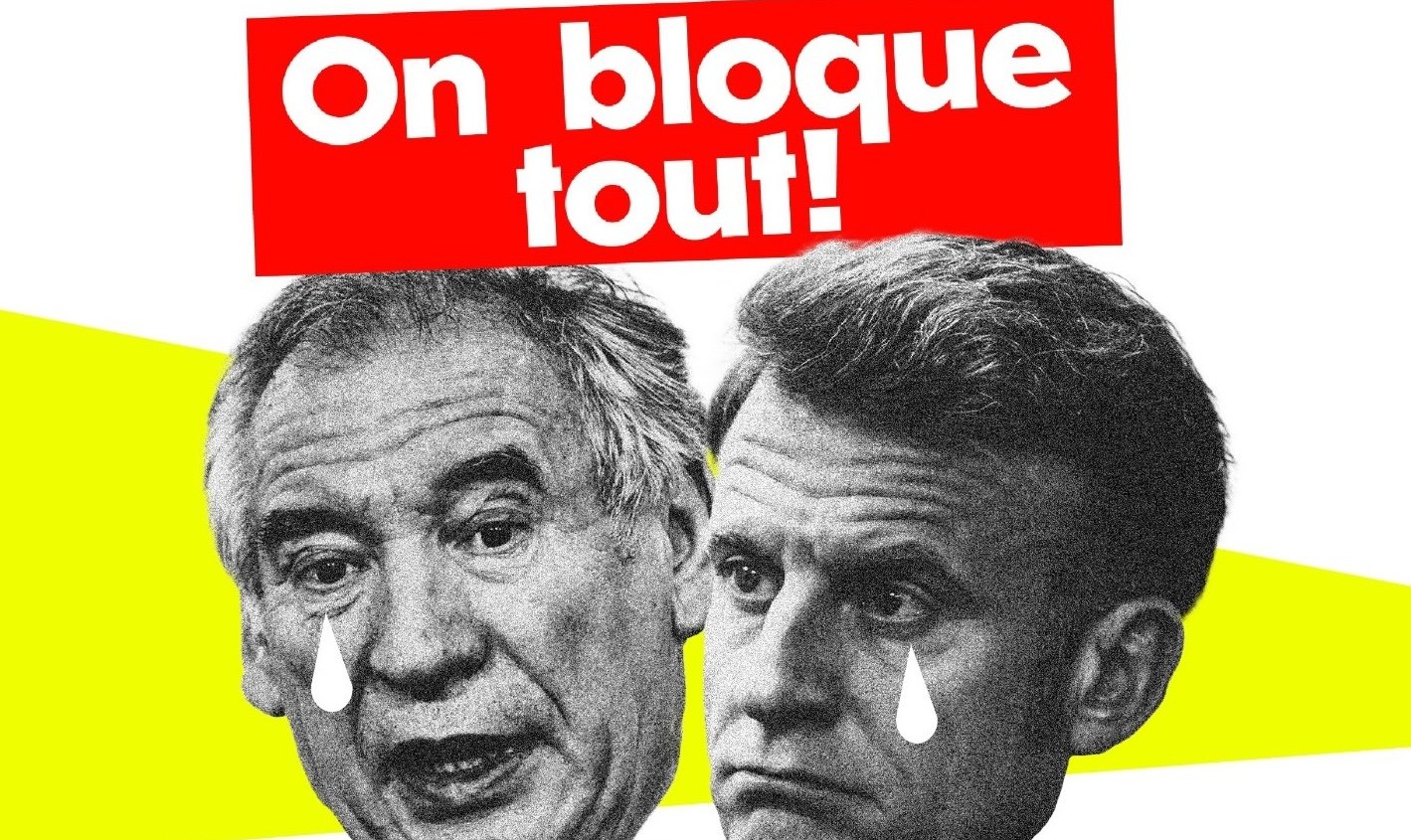

“On 10 September, block everything!”: That slogan has been gaining traction online since French Prime Minister François Bayrou’s mid-July announcement of €44 billion in budget cuts.

The “bloquons tout” (block everything) campaign, originally launched in May on TikTok, has picked up speed over the summer, amplified by former Yellow Vest collectives, far-left figures, and fragments of the radical right.

Protest demands remain vague or scattered, ranging from pay rises to the resignation of the government. So are the tactics, which include strikes, supermarket boycotts, roadblocks, and even calls to occupy ports and public buildings.

While still modest in scale – around 10,000 people follow its main Facebook and Telegram channels – the movement’s recent endorsement by the far-left La France Insoumise (LFI) and railway workers union Sud-Rail has rattled the political establishment.

Bayrou’s government, already weakened by poor approval ratings ahead of crucial budget negotiations, has convened a security meeting this week.

“I find it worrying,” admitted Valérie Hayer, president of the Renew Europe group in the European Parliament, adding that “much remains unclear” about the movement.

Security services are monitoring the movement, though a source familiar with the matter said there is no current indication of foreign influence.

France’s interior ministry did not respond to a request for comment.

A not-so-grassroots campaign

Though now framed as a backlash to budget cuts, the original “block everything” call appeared weeks before Bayrou’s announcement of austerity measures in a post on a TikTok account called “Les Essentiels France”.

According to Le Monde, the EU-sceptic account gained traction by tapping into online networks tied to veterans of the gilets jaunes (“yellow vest”) protests that rocked France from 2018 to 2020. The TikTok channel and a dedicated website now offer countdown clocks and shareable protest materials.

“It is way more professionalised than what we had seen with the ‘yellow vest’ movement, where people who didn’t know how to use Facebook group suddenly became moderators of pages with hundreds of thousands of people,” said Louise Michel, a PhD student working on post-“yellow vest” mobilisations.

But the movement is also more fragmented, Michel said, and less unifying than protest waves seen during the Covid-era “freedom” marches.

Messaging apps, Telegram groups, and Instagram accounts like grevemanifsblocages10septembre now spread decentralised calls to action and meeting announcements – including one in Paris’ Parc de la Villette on 28 August.

The left moves first

Though officially non-partisan, the movement has quickly attracted left-wing political support.

In a August column in La Tribune, LFI leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon urged his supporters “to place themselves at the service of local collectives” organising the 10 September mobilisation.

According to Michel, LFI activists have already joined protest groups in recent weeks – often under the radar, posing as ordinary citizens.

The Socialist Party (PS) has taken a more cautious stance, saying they are “watching closely”.

“The motivations and tactics are still unclear, but we understand the exasperation behind this spontaneous movement,” said PS MEP Chloé Ridel.

Green leader Marine Tondelier declared support but warned against political organisations “instrumentalising the struggle.” Some protesters have already expressed discomfort with LFI’s visibility.

“Some citizens no longer want to take part,” said one user, while another welcomed the retreat of far-right figures.

The far-right in a tight spot

Earlier this summer, some MPs from Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National (RN) saw the 10 September protests as a political opportunity, but the growing engagement of left-wing groups has raised doubts on the far right.

They had hoped to bring to the streets the popularity of the viral “Nicolas qui paie” meme – a symbol of the urban, educated thirty-something crushed by taxes and sacrificed (at least in their view) for the benefit of foreigners.

The RN also sought to channel the energy of the Gueux (Beggars) movement, which denounces so-called “punitive environmentalism” and criticises state subsidies for renewable energy.

“Are we heading towards a popular mobilisation?” RN MP Matthias Renault asked in July.

But by August, he was complaining that “the left has taken over 10 September”.

MEP Matthieu Valet said he supported “working France, which will make its voice heard on the 10th”, but preferred to “fight the street battle in the National Assembly”.

The far-right party now finds itself torn between projecting credibility as a party of government and responding to anger among its voter base – with some grassroots members likely to join street protests regardless of party line.

Increased calls for strikes

Regardless of turnout on 10 September, Bayrou’s government is bracing for a tense autumn as calls for demonstrations against the austerity plans for the 2026 budget mount.

Sud-Rail has called a strike on the same day. Meanwhile, taxi drivers, angry over changes to medical transport rules, plan to “bring the country to a standstill” on 5 September with actions targeting fuel depots, train stations, airports and even the tourist-packed Champs-Élysées in Paris.

Pharmacists, furious over proposed cuts to medicine reimbursements, will close shops on 18 September and every Saturday from 27 September onward.

In Paris, labour groups at 38 public hospitals – representing around 100,000 health workers – will hold assemblies on 25 August to decide whether to join the wave of strikes.

All major trade unions will meet on 1 September to coordinate. The head of General Confederation of Labour (CGT), Sophie Binet, has not ruled out taking part in the day of action on 10 September, although she has stressed that her focus is on ensuring that the mobilisation is “sustained over time”.

Bayrou’s government, however, may face trouble sooner than later. The LFI has announced that it will table a motion of no confidence on 22 September, the first day of the parliamentary session.

(cs, bts)