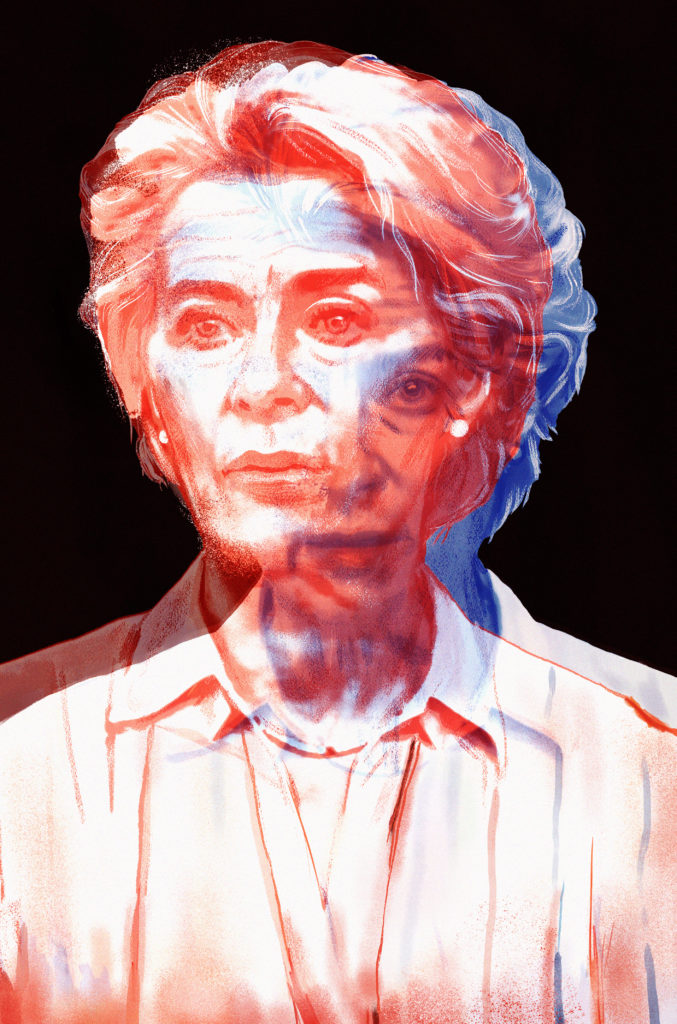

Europe’s American president: The paradox of Ursula von der Leyen

European Commission chief’s top-down approach has endeared her to Washington but alienated colleagues in Brussels.

By Suzanne Lynch and Ilya Gridneff

Illustration by Lucas Peverill for POLITICO

Ursula von der Leyen’s whirlwind tour of the United States started in New York at the United Nations General Assembly, where she rubbed shoulders with the world’s most senior leaders, from U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres to Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

From there, the president of the European Commission was whisked across the Hudson River and into New Jersey, to Princeton University. In a wood-paneled hall in one of America’s most storied Ivy League schools, she delivered a keynote address billed as “Europe’s Moment” that was in reality more of an ode to EU-U.S. relations.

“I have been in politics now round about 20 years,” she told the students, as the camera — whether by accident or design — silhouetted her against a giant American flag. “Never ever have I experienced such an intense, trustful and detailed cooperation with the White House.”

“I think the saying is right,” she continued. “When you face a crisis, you know who your true friends are.”

Von der Leyen’s words were more than just the diplomatic niceties expected of top diplomatic officials in moments like these. According to multiple officials in Brussels and Washington, they reflect how the Commission president has emerged as the person to call when U.S. officials want to call Europe — in particular when it comes to the war in Ukraine.

They also speak to growing murmurs of discontent at home — grumblings from officials in her own institution and among representatives of EU countries about her top-down approach. Von der Leyen’s penchant for secrecy and her dependence on a small coterie of advisers, her detractors complain, runs counter to the EU’s culture of consensus-driven decision-making.

“She doesn’t trust anyone; she lives in a tower,” said one member of a commissioner’s Cabinet, speaking on condition of anonymity in order to speak freely about the institution’s top official. “She doesn’t build alliances. Sometimes that can lead to mistakes as she doesn’t sound people out enough.”

Wartime leader

The spur for the rapprochement between von der Leyen and Washington was Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine.

Hopes had been high in 2020 that U.S. President Joe Biden’s election would reverse the bitterness of the Trump era. But the return to transatlantic harmony had not been smooth — even before Biden’s inauguration, his team made it clear that they were furious about an EU decision to enter an investment pact with China. Tensions persisted over trade, international taxation and the rules governing the digital sphere — particularly those regarding privacy in intercontinental data transfers.

Rumors of war largely swept those disagreements away. By late 2021, as Europe and the U.S. began to emerge from the COVID crisis, another grave prospect was looming: Russian troops massing at the Ukrainian border.

In November 2021, von der Leyen made her first visit to the White House. Among those in the meeting in the Oval Office that afternoon were Biden’s National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, then Deputy National Security Adviser for International Economics Daleep Singh, and Amanda Sloat, then senior director for Europe at the National Security Council.

With von der Leyen were two of the Commission president’s closest confidants, Bjoern Seibert, her head of Cabinet who has worked with her since her days as German defense minister; and Fernando Andresen Guimaraes, another member of her Cabinet who had previously served as head of the Russia, and the U.S. and Canada divisions in the European External Action Service, the EU’s diplomatic service. Also present was EU ambassador to the United States, Stavros Lambrinidis.

Putin’s invasion was still two and a half months away, but tensions were already rising. The two teams discussed the situation on the EU’s border with Belarus, where migrants from the Middle East were being flown in by Belarusian dictator Alexander Lukashenko to cross into Poland and Lithuania.

Then the topic turned to the possibility of a Russian assault on Ukraine. Just before the meeting, Biden had been briefed by national security and intelligence officials about the buildup of Russian battalions near the Ukraine border. He wanted to sound the alarm.

“The president was very concerned,” said one European official, speaking on condition of anonymity. “This was a time when no one in Europe was paying any attention, even the intelligence services.”

Further meetings followed, including a visit to Brussels by CIA Director Bill Burns later in the month, as Washington became increasingly frantic about the lack of urgency in European capitals about the looming threat.

At the instigation of the White House, officials from both sides of the Atlantic, including U.S. Undersecretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland, started meeting weekly by video conference.

As fears of a Russian invasion grew, talk turned to preparations for a package of sanctions that could be adopted by EU countries if Moscow decided to send troops across the border. Contacts started taking place daily. In particular, Singh and Seibert built a close working relationship. Officials from various Commission departments — known as directorates general — were also drafted in, including a group set up under the recently created EU-U.S. Trade and Technology Council, which dealt with the complex issue of export bans.

Seibert was “critical” to the success of the first sanctions package, a senior U.S. official said. “The essential interlocutor with the European Commission was Bjoern Seibert,” the official said, describing the German civil servant as an expert on substance and “a pretty savvy political operator.”

“We had a tremendous amount of convergence across the board,” the official said.

Seibert was the person who rang von der Leyen, who was attending the Budapest Forum in Warsaw, at 4 a.m. to tell her about the invasion in the early hours of February 24.

Throughout the preparation process, it was the Commission that had taken the lead on sanctions, consulting some national capitals like Berlin, Paris and Rome — but for the most part meeting representatives of member countries in small groups to sound out their views.

Fearful that the ambitious package of sanctions could leak, the Commission never provided a draft text, until the final moment when member countries were poised to consider it. The sanctions needed unanimous approval by EU countries, but with their respective publics watching the Russian buildup in alarm, the representatives of national governments in Brussels had little choice but to waive them through.

“It is unlikely that the very close collaboration we are seeing on sanctions and other fronts would have developed as it has without considerable rapport between Washington and Brussels — at the highest levels, but also at working levels,” said Ian Lesser, vice president of the German Marshall Fund of the United States.

Ursula von der Leyen delivers a keynote address at Princeton last month | The Trustees of Princeton University via European Commission

‘Don’t forget us’

Von der Leyen’s strengths — her discretion, her rapid decision-making — may have endeared her to her counterparts on the other side of the Atlantic. But those same attributes have also alienated her from some of her colleagues in Brussels and other European capitals.

During the high-stakes sanctions talks, von der Leyen’s qualities were just what was needed to shove complex, politically sensitive measures through the EU’s slow-moving decision-making processes.

“There was a sense in Washington that this was someone who could finally get things done, who could deliver,” said a senior EU official who participated in transatlantic discussions. Von der Leyen’s experience as a former defense minister also made her the ideal point person for the Biden administration as it warned of a looming war.

But while EU countries were prepared to give the Commission leeway in the first rounds of sanctions discussions, as talk turned to further measures, some national officials began to push back against her hard-charging approach.

When von der Leyen announced a sixth round of sanctions, including a proposed ban on Russian oil, to the European Parliament before members had even discussed it, some were critical. Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte criticized the Commission for its lack of precision on the technical detail. It would take another month before the package was approved, and not before concessions were made to some Central and Eastern European countries on oil.

It wasn’t the first time the Commission president had been rebuked for getting out ahead of the pack. At the height of the COVID pandemic, the Commission’s proposal for a €2 trillion economic rescue package leaked before leaders had seen it, prompting a rebuke by Angela Merkel. “Don’t forget to talk to us,” the then German chancellor told her former protégé.

A three-time Cabinet minister, von der Leyen became the first female European Commission president in 2019, after being catapulted into the job over the objections of many in the European Parliament who had favored the so-called Spitzenkandidat system, which proposes that the post be given to one of the candidates nominated by a pan-European party.

Her decision to ensconce herself on the 13th floor of the Berlaymont EU headquarters, where a former washroom was converted to a bedroom when she took office, has led some to complain that she has governed with a bunker mentality, with the help of only a small group of advisers.

Simmering tensions between von der Leyen and the rest of her 27-strong College of Commissioners burst into the open in June, after she decided to green-light the disbursement of EU recovery funds to Poland, despite concerns over Warsaw’s abuses of the judiciary.

After von der Leyen’s decision was put on the College’s agenda on June 1, five commissioners — including Commission Vice Presidents Frans Timmermans and Margrethe Vestager — put their discontent in writing. The objection by Vestager, who has had a good working relationship with von der Leyen, was especially notable.

“This was not a decision that had very wide support within the College,” a Commission official told POLITICO. “There was a feeling that von der Leyen had probably first agreed to something with the national leaders concerned, without taking account of the views of the Commission.”

Despite her colleagues’ objections, von der Leyen — who declined to be interviewed for this article — pressed ahead anyway.

Central power

Ursula von der Leyen differs fundamentally from her predecessor Jean-Claude Juncker — a notoriously political operator who regularly took the pulse of his colleagues before making decisions | Thierry Monasse/Getty Images

People who have worked closely with von der Leyen say her tendency to centralize power is most evident when big decisions are on the table — the green light for Poland’s rescue fund, for example, or a proposal to classify investments in nuclear or gas energy production as “green.”

In these cases, she is more likely to consult with the powers-that-be in Berlin or Paris than the European commissioner in charge of the portfolio. Similarly, she sometimes works directly with key individuals within the Commission’s directorates general, effectively bypassing the commissioners themselves.

In her top-down style, she differs fundamentally from her predecessor Jean-Claude Juncker — a notoriously political operator who regularly took the pulse of his colleagues before making decisions, even if much of the policy priorities were set by his chief of staff, Martin Selmayr.

In many ways, von der Leyen displays a U.S.-presidential style understanding of executive power. The Commission has been assuming more authority within the EU for some time. Under von der Leyen, this process has accelerated — with the Commission taking a lead role in big changes of direction, such as the issuance of common EU debt, the joint procurement of COVID vaccines and the introduction of Russia sanctions.

“Within the Commission, this process of centralization that already happened under Juncker has continued,” said Stefan Lehne, a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe. “The real power is with the president. Individual commissioners have lost a lot of power; the collegium as such is weaker, the president is stronger.”

Von der Leyen’s guardedness and centralized decision-making process have prompted much speculation in Brussels about her next move. A close relationship with Washington would be a valuable asset if she were interested in a high-level international job, for example at the United Nations. Interestingly, von der Leyen was one of the first to congratulate Biden in August in a late-night tweet when he signed his signature domestic legislation, the Inflation Reduction Act — despite the fact that the EU has some major concerns about the proposal, which it views as protectionist.

Alternatively, a desire to serve a second term as Commission president in 2024 would help explain why von der Leyen has sometimes kept better contact with national capitals, whose support in the European Council she would need, than with her own Commissioners.

“Von der Leyen pushed through the Polish recovery plan against serious opposition from the very top of her College,” said Daniel Freund, a member of the European Parliament with the German Green party. “She went against the majority of the European Parliament when it comes to the rule of law, up to the point where we had to sue her for inactivity.”

“You might win singular battles with this approach but you will lose support in the long run,” Freund added.

Just this week, two commissioners, Thierry Breton and Paolo Gentiloni, called for a support fund to help cushion the blow for Europeans during the current energy crisis — something that had not been promulgated by von der Leyen.

The question for von der Leyen is whether her top-down approach will continue to pay dividends if and when the crisis subsides and attentions turn to long-term concerns or decisions that require broad levels of support.

Her ability to push through sanctions was helped by the fact that few others in Europe were paying attention. The U.S. was getting little response from national capitals to their warnings about Putin’s intentions. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz and French President Emmanuel Macron had other things on their mind — Macron was fighting a reelection campaign and Scholz was trying to keep an increasingly divided three-party government together.

Meanwhile, Brexit had deprived the EU of one of its main intelligence assets — with Britain, a member of the “Five Eyes” intelligence alliance no longer participating in the bloc’s discussions.

Sanctions were also an area where the Commission had real heft, given the power of the EU single market and the EU’s economic interrelationship with Russia. The highly technical nature of the discussions suited the strengths of Seibert’s detail-focused team.

But alienating her College is risky business. There’s the danger her approach, and her close ties to Washington, could store up difficulties for her when she tries to get other EU policy priorities through.

Brussels and Washington are still far apart on issues like potential trade agreements or the regulatory framework to protect privacy in data transfers across the Atlantic. And then there are EU-specific priorities like reforming the EU’s fiscal rules and implementing the Commission’s Fit for 55 climate change package. On issues like those, where there are no Russian troops to focus minds in Europe, von der Leyen may find that what she needs is not the support of Washington but of colleagues closer to home.